It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Racines was going to have a long, drawn-out, happy goodbye. In its 36 years, the restaurant made many friends, and owners Lee Goodfriend and David Racine thought they had built in plenty of time for those folks to say farewell when they announced Racines’ closure nearly a year in advance. But the pandemic forced the pair’s hand, and in the summer of 2020, they decided to remain closed rather than limp along, officially calling it quits six months earlier than planned.

“Never did I think it would happen like that,” Goodfriend says. “We were planning on reopening, but because of our ages, we didn’t want to get back into serving the public during the pandemic. Then opening and closing costs money, so we thought it was cheaper and healthier to stay closed….It’s bittersweet.”

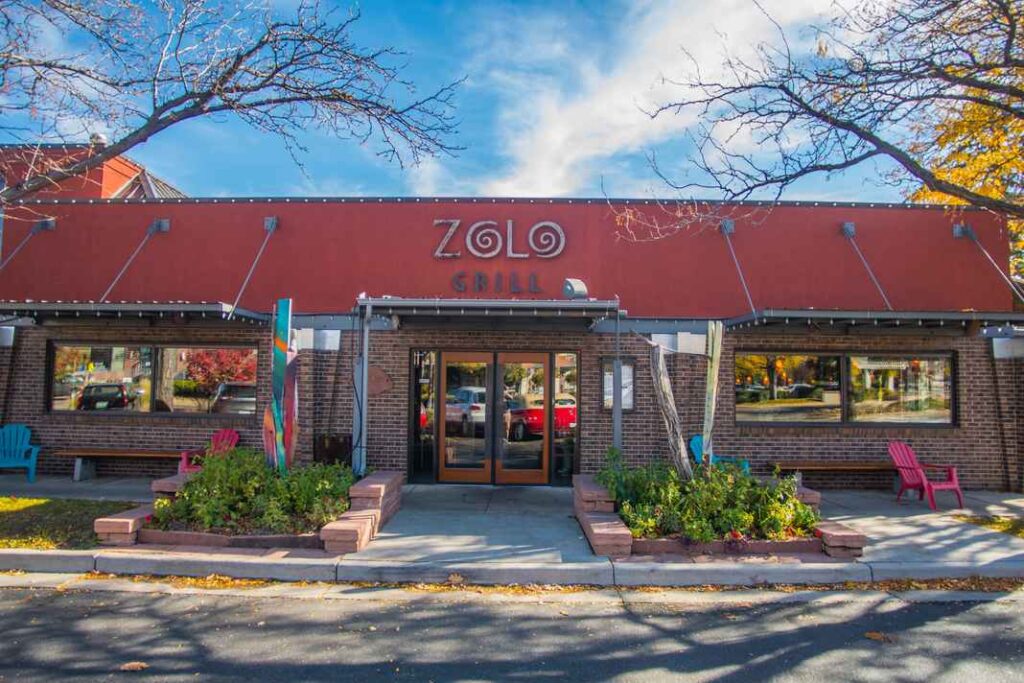

It’s the end of an era for other mainstays, too, including Vesta, the Market, 20th Street Cafe, Zaidy’s Deli, and El Chapultepec in Denver, and the Med and Zolo Grill in Boulder. Other veterans have closed up and announced uncertain reopenings, like Denver Diner, Greeley’s JB’s Drive In, Aspen’s the Red Onion, and Colorado Springs’ Fargo’s Pizza. All of them have achieved iconic status, serving their communities for generations, inspiring countless restaurants, and growing and developing their local dining scenes. The decision to close these spots is one of the heaviest their owners will ever make, and it’s so painful for some that they declined to speak with DiningOut. After all, these are the places into which they’ve poured their hearts and souls for most of their adult lives, and the grief that comes with closing is raw and real.

“I never expected the outpouring I got when I closed the Market. I probably got 150 hand-written letters to my address—pencil drawings and paintings of the Market; pictures of me with customers,” says Mark Greenberg, owner of the late Larimer Square espresso bar, bakery, and deli. “I had customers who came in from the first day I started and kept coming in. They were there every morning sitting at the same tables. It was like kindergarten.”

Greenberg’s decision to close the Market was abrupt for any restaurant, but especially for a 37-year-old icon. “It was a spur-of-the-moment decision,” he says. “I wasn’t planning on retiring that quickly. [But] I didn’t want to deal with the government and all these [COVID] regulations.”

So on that infamous day in March 2020 when Governor Jared Polis announced the closure of Colorado restaurants’ dining rooms, Greenberg went home to his wife and told her she’d be seeing a whole lot more of him. With $33,000 monthly rent and no way to pay it for the foreseeable future, Greenberg knew it was time to close the doors for good.

“MY KIDS GREW UP WITH ME IN THE MARKET, BUT THEY ALSO SAW HOW MUCH STRESS THE RESTAURANT BUSINESS CAN PUT ON SOMEONE.”

Mark Greenberg, the Market

He was let out of his lease within the week and was given a couple months to clear out. He unloaded kitchen equipment however he could (with so many restaurants shutting down, the resale market blinked out overnight), and donated all his food to Denver Rescue Mission.

“It was horrendous. There were days of tears,” he says. “Getting rid of everything was very traumatic. When all was said and done, there was nothing left in the building. I went down there once a week to collect the mail in an empty store I worked in every day for 37 years. Every time I went in there, I was so upset.” At the end, Greenberg, his wife, children, and grandson met at the empty restaurant for one last breakfast. “It was a somber situation, and a very emotional day for me,” he says. “My kids grew up with me in the Market, but they also saw how much stress the restaurant business can put on someone.”

The restaurant business, an already notoriously difficult one, has become increasingly challenging in recent years. Property, rent, wages, food, technology, and seemingly every cost associated with operating a restaurant have risen sharply. “That entire year before [the pandemic] was a tough financial year for me because of wages and things getting so high in Denver,” Greenberg says. “Everything was escalating to a point where it wasn’t profitable anymore. I’ve worked way too hard; I’m 67. I never didn’t like going to work for 36 and a half years. The last six months of going to work became tiresome.”

Greenberg says the Market’s general manager thought about reincarnating the cafe at a new location, but ultimately deemed the venture too risky. The staff was another consideration for Greenberg, who says more than half of his employees worked for him for an astonishing 25-plus years. “It was kind of a family in the business…I gave people careers who had no career before. That’s what made me feel good,” he says.

The talent that came out of these seasoned restaurants remains part of their legacy. After the Market shuttered, former employees Viviana Villagrana, Laura Madrid, and Audrey Daniels started Lala’s Bakery, and they can’t bake their take on the Spring Fling cake fast enough. Kevin Taylor, an iconic chef himself, worked for Racines near the beginning of his career, and Zolo Grill taught Hosea Rosenberg (Blackbelly, Santo), Jen Bush (Lucky’s Bakehouse), and James Lee (the Bitter Bar) the ropes. “We had a lot of chefs through that kitchen,” says Dave Query of Zolo Grill. “I bet there are 15 people, if not a few more, who have worked at Zolo who went on to own their own restaurants.”

Zolo Grill was Query’s first restaurant in what later became his Big Red F Restaurant Group, which now operates 13 spots. Query pulled the plug on the Southwestern restaurant in late November after 26 years. The decision was hard and painful—Query says Zolo had a stronger contingent of regulars than any of his restaurants, and that its employees, past and present, had a bond like no other. Like the Market, Zolo’s closure was unexpected. “[It] had been a workhorse for a long, long time, so this wasn’t on our radar,” he explains. “We had just done a remodel three months before the pandemic hit—new furniture, redid the floors. We spent a lot of money rebooting Zolo coming into 2020.”

But the pandemic forced a focus on what was most important, and Big Red F needed to lose Zolo in order to keep the remaining restaurants strong. “It all came down to bandwidth and the ability to keep things working, and it was the one that missed the mark. Twenty-six years is a long time for a restaurant, and it was just time to go,” Query says.

“PEOPLE ARE LONGING FOR THE FAMILIAR. I THINK A LOT OF THESE ICONIC, OLD RESTAURANTS ARE GOING TO DO QUITE WELL.”

Dave Query, Big Red F

A contributing factor to Zolo’s closure, and to those of other restaurants of a certain age, is the demographic it served. Given their longevity, these sorts of spots count older diners as fans: the very group most likely to be staying home due to their risk of contracting the virus. “They’re not interested in getting out of the house for the sake of getting out of the house,” Query says of older diners. “They’re being very safe and protecting their lives and health and the health of others. We definitely saw a slowdown based on that.”

Query says Zolo didn’t pivot as well as his other restaurants, like the more to-go-friendly Post Brewing Co. Instead, he turned Zolo’s kitchen into a sort of cooking headquarters for charitable efforts, where employees prepared meals for Feed the Frontlines Boulder, as well as the Big Red F staff. It may not have been the most lucrative shift, but it made for a nice send-off for a restaurant that introduced so many to New Mexican cuisine.

Also in Boulder, and also abruptly, Peg and Joe Romano closed the 27-year-old Med in June 2020. “The decision to close last year was forced on us by the virus,” Peg says. “We had three restaurants (the Med, Via Perla, and Brasserie Ten Ten) that were very popular and wildly busy that overnight became completely empty. That was a shock in itself. The sadness of the situation during that time was immense.”

When restaurants were allowed to reopen for dine-in for up to 50 people in summer 2020, the Romanos didn’t see how that would work financially for the Med, which seats a total of 525. Combined with a menu not conducive to takeout, the approach of colder months, and the still-raging virus, the couple couldn’t see an economical way to sustain their restaurants and staff. Reluctantly, they closed all three.

“This decision was hard, sad, and not really what we wanted to do, but operating a business with no or very few customers—it just wasn’t something we thought we could do. We felt it was the only decision we had at the time,” Peg says. “We are overwhelmed by the love for the Med. That it became a Boulder icon seems accidental, but with 27-year staying power, I guess that’s what can happen. We are very proud of that reputation.”

(ED: Word on the street is that the Med will be reopening later this year under the same name but different ownership.)

In Colorado Springs, Dave Lavin hopes that 47-year-old Fargo’s Pizza, which he owns with his wife, Paula, and brother-in-law, Evan Gardner, will make it through COVID. But because of capacity restrictions, the family made the decision to put the restaurant on hiatus in December.

“The restaurant has been profitable from the day it opened in 1973. This year, however, things changed dramatically, and we had to make the decision whether we wanted to feed it cash-wise month after month for an indefinite period of time, or mothball it until things turn up. We chose the latter,” Lavin explains.

“WE HAVEN’T GIVEN UP THE SHIP AT THIS POINT.”

Dave Lavin, Fargo’s Pizza

Fargo’s seats 500, and the 50 percent dine-in cap just didn’t cut it. Because of the restaurant’s large footprint and extensive staff, the upkeep was costly. Lavin cites recent minimum wage increases—with 100,000 annual staff hours at the restaurant, every dollar jump equates to an additional $100,000 in expenses—as yet another mountain to climb.

“While revenues were still increasing year over year, costs were going up faster than revenue,” he says. “Our intent, though, is to reopen when things look promising. We just don’t want to open up prematurely. We don’t know what the future brings, but we haven’t given up the ship at this point.”

While the pandemic has become—and rightfully so, in many cases—an easy scapegoat for restaurant closures, it’s not the villain in Racines’ story. “We have an unusual situation in that we decided to sell before the pandemic. Dave and I were both turning 70, and Racines was such a big, expensive place to run. It was getting harder and harder to make any money. We thought it was time to get out,” Goodfriend says. They sold the Sherman Street building to a real estate developer that plans to blitz the structure and erect a 13-story apartment complex in its place.

While tearing down the longtime neighborhood favorite to build fancy apartments may feel like a gut punch, Goodfriend says selling the building was always the plan. When she and Racine moved the restaurant from its original location on Bannock Street to Sherman Street in 2003, they bought the property with the intention of selling it and retiring within 15 to 20 years. That’s the thing with older restaurants; their owners are older, too. They’ve worked hard their whole lives, and while it’s painful to end that chapter, they’re ready to move on.

Despite the challenges and the closures, Big Red F’s Query believes that longtime restaurants still hold an important place in our dining environment, and that they may even experience a post-COVID resurgence. “People are longing for the familiar. I think a lot of these iconic, old restaurants are going to do quite well. We’ve all gotten rocked to our core, and getting back to that comfortable place where you’ve shared a lot of experiences, going back to that is going to feel like slipping into a pair of warm slippers after a full day of skiing,” he says.

But for those not coming back, the run was a good one. From the careers they kickstarted, the people they fed, and the lives they changed through a green chile omelet or a fruit-flecked cake, these classics will be remembered, celebrated, and forever missed. In a way, they’re the standards, the decades-long neighborhood institutions that so many restaurants hope to become.

Talk to us! Email your experiences (and thoughts, opinions, and questions—anything, really) to askus@diningout.com.

Related

About The Author

Comments are closed.