Forward Motion

What it takes to move the needle on a dining scene

When Melissa Strong moved from New Orleans to Estes Park in 1996, she had plans to become a college professor. But first, she wanted to sink into the rhythm of the Rocky Mountains, do some rock climbing, and take a breather. To pay the bills, she took a restaurant job—never guessing that she would fall into the industry and never leave.

She started climbing and realized that this was her passion. She was good at it, too. Soon Strong had sponsors knocking on her door and she was on the rise as an elite athlete. She waited tables, bartended, and managed restaurants on the side. Life was good—great, even—but something was missing. “I was raised in an Italian family and I love food, and the food scene here was lacking,” she laments. Menus in Estes Park, like many mountain or resort towns, are tourist driven and laden with uninspired bar food, pizza, and steak. “You knew what was on every menu because it didn’t change,” she says. “It bothered me that the bar was low.”

On her days off, Strong would drive the 50 minutes to Boulder, or even the hour and 20 minutes to Denver, to get her fill of creative eats. Along the way, she saw the farm-to-table food movement emerge and an idea began to germinate: Strong would open a restaurant. “I love food, I love my community, and I didn’t want to wait for something or someone to come from Boulder to save Estes Park,” she says.

“I love food, I love my community, and I didn’t want to wait for something or someone to come from Boulder to save Estes Park.”

Melissa Strong, Bird & Jim

And so, in 2016, she bought a rundown space and began renovations. Its name would be Bird & Jim, after Isabella Bird and Mountain Jim, two local legends from the 1800s who embodied the hearty, nothing’s-gonna-stop-ya mountain spirit. The name was prescient, and Strong couldn’t have known she would soon need to draw on that very same grit. A few months into the project, she was electrocuted while redoing furniture for the restaurant and nearly died. Despite recovering from severe electrical burns, the loss of multiple fingers, and a number of serious surgeries, she was still determined to open Bird & Jim.

From her hospital bed, Strong picked out paint colors and lighting, made interior design choices, and hired staff, all using voice dictation. Six excruciating months later, Bird & Jim’s doors swung open. “You put everything into it. You put all your dreams, huge debt—I literally put my fingers into it—and you just hope people come,” she says. “I thought it was going to be too nice for Estes Park. But we’re rustic and modern at the same time.” Maybe it’s because the community rallied around Strong (more likely it’s because Bird & Jim filled a niche that the town desperately needed), but the restaurant pulled in more money than Strong projected in its first year. In 2019, it saw 30 percent year-over-year growth, and in the first quarter of 2020, just before COVID bore down, sales were up 20 percent. “I can’t say we were an instant success, but it was working.”

“I can’t say we were an instant success, but it was working.”

Melissa Strong

Phil Armstrong knows that tug—that need to push something forward. He’s done it in Steamboat Springs with his restaurants Aurum, Table 79, and Periodic Table, then in Summit County with Aurum Breckenridge, and now in the Roaring Fork Valley with the newly opened Aurum Snowmass. But the idea of growing a dining scene wasn’t how things started out. When Armstrong moved to Steamboat in 2014, it was because the opportunity presented itself. “I was looking to do my own thing and [the decision] was born out of the location and the details,” he says. “I didn’t target Steamboat back then, not because I didn’t want to reshape it, but it was more about the partnership and the deal.”

Since that time, Armstrong has had an impressive impact on Steamboat and Breckenridge’s restaurant fabric. Aurum strikes a balance of upscale and trendy while also feeling like a staple, but it wasn’t always that way. “[In Steamboat] we started much higher-end than what we are now,” Armstrong says. “We let the customer drive the use of space.” Armstrong recalls the pushback he received when he first arrived in town. His restaurant credentials came from time in Denver, and the locals felt he was bringing his big-city ideas to their town. Perhaps he was—but he listened, backed off a little (while still nudging forward), and has had great success. “As we grew in Steamboat with Table 79 and Periodic Table, so did the entire dining scene change,” he says.

When Armstrong opened Aurum Breckenridge in 2016, the experience was entirely different. The town, the residents, even the other restaurants greeted him with open arms. It was as if the scene was just waiting for something to up the ante. “Here’s this town: there’s crazy volume, places are packed, but the bar is pretty low,” he says. When he’d tell outsiders he was opening a place in Breckenridge, they would say there are already so many restaurants. He would respond with yes, but there’s room. And there was. “When we decided to open there, the dining scene was like ‘Oh, my god, thank you. Here’s a restaurant that acts the part, tastes the part,’” he says. (I was living in Keystone when Aurum Breckenridge opened and can vouch for this.) As for the warm welcome from fellow restaurateurs, Armstrong gives credit to the strength of the restaurant association in Breck. “The community aspect in Breck is really there,” he says. “Our Steamboat association isn’t that way.”

“Here’s this town: there’s crazy volume, places are packed, but the bar is pretty low.”

Phil Armstrong, Aurum, Table 79, and Periodic Table

The newest Aurum, which opened in Snowmass in December, has real potential to be a kick-starter. Snowmass, which perpetually plays second fiddle to Aspen, has never been a dining destination. But the arrival of Aurum, along with Kenichi (a longtime Aspen sushi favorite), marks a turning point for the community. “This year is the year we are coming onto the dining scene in a way we haven’t before,” says Sara Stookey Sanchez, public relations manager for Snowmass Tourism. “What’s moving us forward is that we don’t have a celebrity chef focus, [but] we have a staple restaurant group like Aurum or a well-known valley entity like Kenichi. That’s what people know and trust, and they’ll think of Snowmass as having those standouts.” Armstrong is equally excited. “I’m cautiously optimistic that Snowmass Aurum might catch some attention,” he says. This third Aurum has also come to encompass his growth strategy: “We could go to Park City, but there are already great restaurants in Park City,” he says. “I think that’s a purposeful thought: Where can we go to define a scene?”

For longtime Denver chef Duy Pham, rubbing up against the boundaries of a scene has always been his way—sometimes to his detriment. “It’s a balance I struggle with, especially when I was younger,” he says. Pham’s career spans decades and has taken him from the epicenter of Denver dining in the ’90s (he cooked at the beloved and now-shuttered Normandy and Tante Louise) to Pueblo to Parker and back to Denver. Those three cities stand in sharp relief against each other—and Pham has cooked in and helped push each one forward.

He brought high-end French food to Pueblo via now-closed Restaurant Fifteen Twenty-One. He utilized sous vide at the late Epernay Lounge in downtown Denver just as the technology was making its mark. He championed large-format dishes like a $75 tomahawk steak for two in Parker long before the town embraced (or had even heard of) such a thing. “That’s always been my problem,” Pham says. “I always want to see the next vision and trend before it hits, and then I launch it too quickly. When you’re the pioneer, people don’t understand you.”

In Pueblo, he hoped there would be enough of a population to support fine French cuisine with a farm-to-table backbone, but the restaurant was quickly ruled a special-occasion spot. It was a hit with high-income diners working in pharmaceutical and medical industries, but a reach for others. Ultimately, Pham toned it down even as he refused to bend on his commitment to local ingredients and purveyors. “We made it more homey, more farm-to-table,” he explains. “That was a fun progression and I still think it was pushing people out of their comfort zone.” Pham opened Parker Garage in Denver’s southern suburb with an ambitious menu that leaned on large shared plates, and the guest wasn’t ready for it. But now, several years in, the customer is not only accepting of large-format dishes, but is all-out demanding that tomahawk steak.

“We made it more homey, more farm-to-table.”

Duey Pham, Foraged and Parker Garage

Over time, Pham has refined his guiding principle and he practices it at his current restaurant, Foraged (located on Denver’s Dairy Block). Rather than this is what we want you to understand, he’s flipped the equation: understand what they want first. “Ease [diners] in, gain their trust, then start pushing,” he says, with a smile in his voice.

In 2017, when chef Brian “Bob” Brouillard began commuting from Vail to work at Craftsman and Hovey & Harrison in Edwards, he said it felt “like [he] was driving to Utah.” Edwards was so removed from Vail’s bustle that it didn’t feel at all connected. Today it’s a different story. The town—and its dining scene—have grown by leaps and bounds. And thanks to Hovey & Harrison and Craftsman, Edwards has become a dining destination in its own right.

Initially, it was a challenge to run a farm-fresh daytime market, cafe, and bakery—something H&H co-owners Gretchen Hovey and Molly Harrison had dreamed up based on their love of and dedication to excellent ingredients. “You always want to cook what you want to cook, but that’s not what always pays the bills,” Brouillard says. “People wanted certain things, staples like egg sandwiches, breakfast burritos, yogurt bowls.” Harrison put shakshuka on the menu but no one ordered it. Ditto the congee. Ditto the fried baloney sandwich made with a glorious hunk of River Bear mortadella. “It takes time to get people to try things,” Brouillard continues. And it takes education and exposure. It took a write-up in the Vail Daily to turn people’s attention to the shakshuka. “That was such a dud, but now we can’t keep up with prep.”

Over the years, Brouillard has seen a different diner emerge: not just a more adventurous local, but also the customer from Vail or the traveler along the I-70 corridor who specifically seeks out Hovey & Harrison’s offerings. Chris Schmidt of Craftsman has seen it, too. “When I first left Sweet Basil, this place was desolate,” he says. “Now look at this center. We’ve all helped each other.”

Hovey & Harrison and Craftsman took it upon themselves to bring a chef’s perspective (and persuasiveness) to Edwards. And while Hovey & Harrison’s egg sandwich will never come off the menu, that staple has steadily built loyalty and paved the way for evolution. “We don’t want to be stagnant,” Brouillard says. “We want to keep pushing and pushing.”

“We don’t want to be stagnant.”

Brian Brouillard, Craftsman and Hovey & Harrison

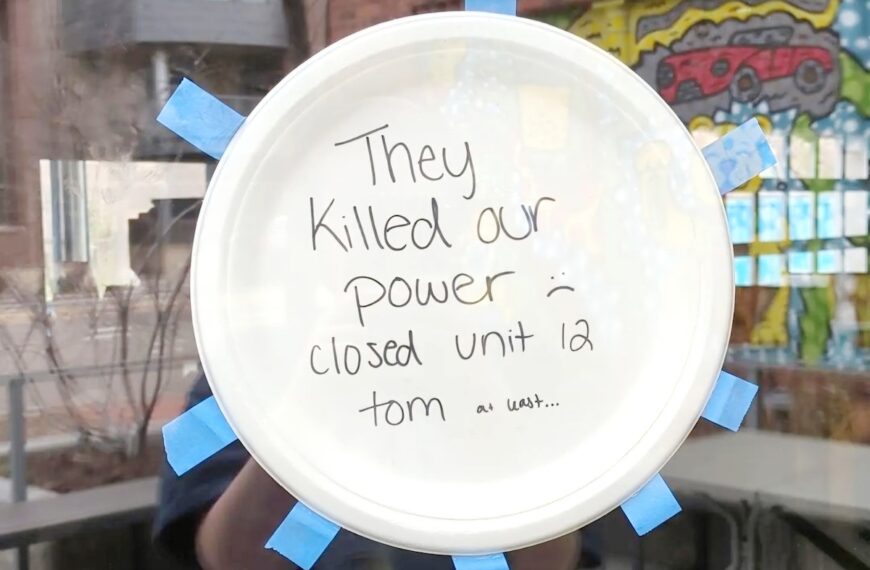

Estes Park, Denver, and towns like Steamboat, Breckenridge, Snowmass, and Edwards have seen unprecedented growth. And with that expansion comes stronger and more textured restaurant scenes, thanks to the culinary pioneers who dug in their heels and staked their claim. In Estes Park, Strong is opening a new place—a bakery, because the town doesn’t have one—that will serve breads, pastries, coffee, pizza, and grab-and-go sandwiches. Strong has also watched as Big Red F Restaurant Group brought the Post Chicken & Beer to town. Rather than eyeing the outsider with suspicion, she’s elated. “I raised the bar for Estes. [It’s amazing] when you take many years of dreams and it actually happens,” she says. “We’re growing this part of the Front Range.”

In Summit County, Aurum’s upscale eats paved the way for Rootstalk, a high-end, ingredient-forward restaurant that chef Matt Vawter opened in Breckenridge a little over a year ago. And now, along with growing the Aurum brand, Armstrong has another Breckenridge project in the works: The Carlin, a boutique restaurant and hotel modeled after the European inns he frequented when ski racing across the pond. “I feel like we’ve helped shape that town, and the Carlin will add to that.” And so it goes in Denver, in the Vail Valley, and beyond. Where there are pioneers (aka stubborn and determined chefs and operators), there are sparks of innovation. Sometimes it burns slowly and sometimes it catches on right away, but across Colorado, culinary boundaries are being pushed outward in order to usher in the new.

Ad:

Comments are closed.