When David Borrowman started raising pastured Berkshire hogs in 2015, he began with 15 animals and boundless dreams. He’d read stacks of Joel Salatin books on sustainable family farming, and after several years of travel, he was ready to sink some roots back home in Missouri. So Borrowman became a farmer, raising his own corn for feed and letting his hogs “mess around” outdoors.

Growth, however, was slow. “I could raise 100 hogs, but moving them is the issue, because there are only so many people in my region that are willing to pay a premium for pasture-raised pork and buy a whole or half hog at a time,” Borrowman explains. Plus, small-scale farming involves a lot more than just raising livestock. “You’re also the warehouse, delivery person, marketing department, accounts manager…. You wear all these hats and you just start to run out of hours in a day,” he says.

“You’re also the warehouse, delivery person, marketing department, accounts manager….You wear all these hats and you just start to run out of hours in a day.”

David Borrowman, farmer

In 2018, hoping to find another avenue for expansion, Borrowman signed on with Niman Ranch, a collective of small, family-run meat producers that follow sustainable and humane practices. The company sells the meat to like-minded restaurants and retail outlets across the country. Niman Ranch committed to buying 50 of Borrowman’s pasture-raised hogs according to a fee structure that adapts to farmers’ costs—so if the price of feed goes up, so does Niman’s payout.

Mixing into the larger company gave Borrowman far more financial security than he had as a tiny producer. That let him quit the side jobs (such as hauling hay and working part-time for the U.S. Forest Service) that he’d needed to supplement his hog operation. And in spring 2021, Borrowman completed construction on a 250-head hog barn. He’d build bigger, he says, if the hilly landscape of his farm didn’t restrict building size. Even so, he’s scouted space for three more of the hoop barns that Niman Ranch endorses for its hybrid indoor-outdoor pork production. One day, Borrowman could raise as many as 2,000 hogs per year, all living without antibiotics but with plenty of pasture and fresh air.

It’s still the sustainable, family-run farm that Borrowman always envisioned, except hitching up to the larger Niman Ranch collective of 750 farms let him scale up his operation for greater environmental impact and financial strength. And those benefits extend beyond Borrowman’s pork. “We’d been expanding our pollinator plantings, which ironically has also been a big push for Niman, so they helped us with the seeding cost for more acres of pollinator plants,” he explains.

Borrowman’s story is typical of the farmers who sell to Niman Ranch. “We know that the collective impact supports so much more than just the meat production,” says Chris Oliviero, Niman Ranch’s general manager. So this year, the company embarked upon two sweeping studies that are intended to complement the anecdotal evidence (such as Borrowman’s example) with quantitative data that measures the multiplier effect. One is an economic study conducted by an Iowa State University agriculture economist that calculates the ripple effects on the rural communities surrounding farms that sell to Niman Ranch. The other is an environmental assessment conducted by the Sustainable Food Lab that analyzes the achievements of the collective’s own farmers.

When the data is released this fall, Niman Ranch expects it to address consumers’ questions about the environmental footprint of its food, and it could also quantify the sustainability and community benefits of purchasing the company’s products. The studies may even substantiate the company’s belief that small can be mighty—if farms’ collective impact includes financial stimulus for local economies, improved soil health for land under production, and better animal welfare. “Partnering with us lets farmers scale up by working together, not just by getting bigger,” says Oliviero.

Niman’s company-to-company affiliations have also spread beneficial change beyond the farmers’ collective. When Perdue Farms bought Niman Ranch in 2015, many feared the larger company would insist on implementing the kind of large-scale economic and environmental efficiencies that the collective had always resisted. Yet the opposite occurred: Perdue ended up adopting some of Niman Ranch’s animal-care practices (such as phasing out the use of antibiotics) and launched an annual animal-care summit that’s open to animal welfare advocates. Niman Ranch is also mentoring Native American Natural Foods (NANF), which was unprepared for the runaway success of its Tanka Bar bison-and-berry meat sticks. The cashless agreement lets NANF benefit from Niman’s marketing, supply chain, and distribution savvy, while helping the collective develop new sources for bison and sustainably raised beef.

“I think it’s important for small, independent producers to find a partner, whether that’s a Niman or a direct-to-consumer site,” says Oliviero, continuing: “Because it’s hard to scale up from tiny to small, and it’s really hard to make your voice heard broadly.”

If you ask Brian Coppom, executive director of Boulder County Farmers Markets (BCFM), about the value of forming collectives of food producers, he’ll tell you it’s one of the only ways farmers can combat the foundational problem in agriculture: consumers’ reluctance to pay the true cost of food. “In order for us to have eggs at $1.50 per dozen, we accept that invisible others will incur the burden, meaning polluted rivers, manure ponds, eroding soil, shrinking biodiversity, poverty wages, and animal suffering,” says Coppom. To survive financially, farmers must dump costs onto those “invisible others” or skim from their own, already-thin profits. But collective partnerships give farmers a third option.

“One way to build value is through collective action, which limits the inevitable race to the bottom when farmers undercut each other,” says Coppom. Some collectives (such as Colorado’s Western Sugar Cooperative) aggregate supply in order to have more market leverage and maximize farmers’ returns. Others (such as Niman Ranch) unify food producers under the banner of ethical or sustainable food production. Still another type of collaboration shares infrastructure costs to increase margins. The BCFM combines the latter types by uniting growers under the banner of local agriculture while also giving them a shared structure for marketing and operations.

“One way to build value is through collective action, which limits the inevitable race to the bottom when farmers undercut each other.”

Brian Coppom, Boulder County Farmers Markets

Yampa Valley’s Community Agriculture Alliance (CAA) is another hybrid-style collective. Headquartered in Steamboat Springs since 1999, the not-for-profit CAA now represents 70 local food producers that rely on the collective to share their stories and introduce them to new sales outlets. Local restaurant groups, such as Rex’s Family of Restaurants and Hannah Hopkins’ Mambo, Bésame, and Yampa Valley Kitchen, have connected with local producers through CAA. Most members emphasize environmentally sustainable production methods. And in the past year in particular, the organization has helped these small, sustainability-minded growers meet the surging demand for local food.

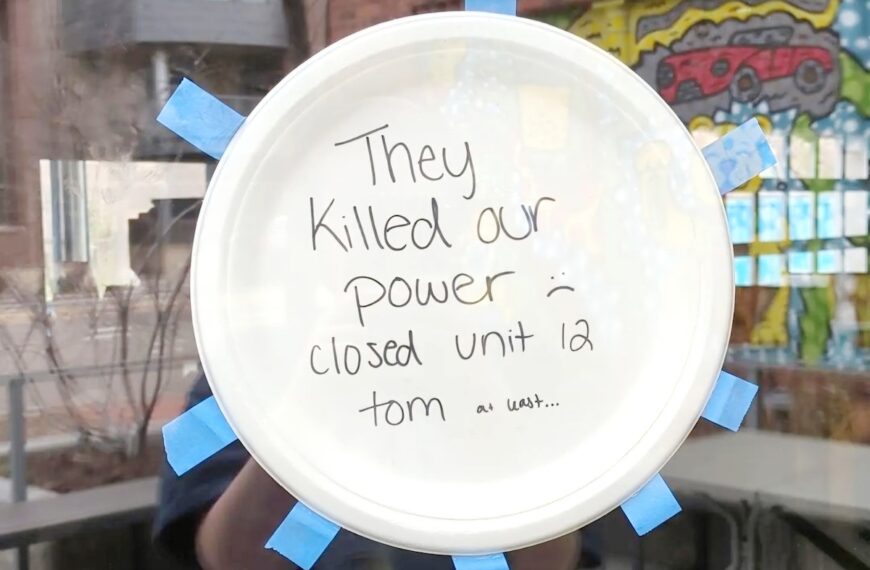

On March 17, 2020, just as the country started closing down in response to COVID-19, CAA expanded its online store to include a brick-and-mortar shop in downtown Steamboat Springs. “All that month, we had a line of people out the door,” says Michele Meyer, executive director. Since then, CAA has processed $10,000 a month in sales of its vegetables, beef, lamb, eggs, mushrooms, pies, and other locally produced foods.

“Our goal isn’t to sell beyond the Yampa Valley. We’ve got all the demand we can handle right here,” explains Meyer. “But we are helping producers expand to meet that demand.” The nonprofit manages sales to individuals and restaurants, so growers don’t have to staff a farm stand or drive around to 20 eateries trying to offload their goods. It also educates consumers about the people and places that generate their food, using online articles and word of mouth in the retail shop. In December 2019, CAA launched a micro-loan program that lets producers borrow from a $10,000 pool to improve or expand operations. Drip irrigation, a hoop house to extend the growing season, and indoor grow lights are among the projects that have been realized with small ($6,000 or less) loans that helped producers make significant leaps forward. The CAA charges less than two percent interest, which is reinvested into the loan pool. “It’s much better than a credit card, which is how most of these projects would’ve been paid for,” Meyer says. The collective is also working on an initiative that would make commercial freezers available to meat producers that need a way to store their products after autumn, when livestock is butchered.

Even producers that can’t or won’t expand their operations find value in CAA participation. Adele Carlson of Sand Mountain Cattle Company, for example, has no plans to grow beyond the 15 to 20 all-natural, grass-fed and finished steers (and 350 cows) that she raises each summer north of Steamboat Springs. But she does need help finding buyers for the full array of cuts produced, from ground beef to steaks to roasts and soup bones. “We can sell our leftover cuts on the ag alliance, and those pieces bring in customers that are interested in buying bulk beef [as a quarter, half, or whole steer],” says Carlson.

Another not-for-profit collective, the Colorado Grain Chain, defines “local” more broadly, since it represents producers across the entire state. But its specific focus is heritage and regionally adapted grains: The collective supplies education and technical support for growers, while also introducing Colorado-grown grain to brewers, bakers, chefs, and consumers.

But it’s difficult to imagine such collectives being successful without nonprofit status, says CAA’s Meyer. “We pay producers full price and charge a 10 percent markup to consumers, and we are not making money,” she explains. “So when people come to us and say, ‘I’d like to open an organic food store,’ I think that’s great, but how high would your prices have to be for that store to make a profit?” She imagines eggs at $10 per dozen—or else producers would have to receive a smaller payout for their food.

Not all collectives are formed at the producer level. Some are ignited by chefs and their suppliers, and that’s how Bangs Island Mussels came to Colorado. Paul C. Reilly, executive chef and co-owner of Coperta and the late Beast & Bottle in Denver, fell in love with these sustainably farmed bivalves when he visited the aquaculturist back in 2012 and discovered how the phytonutrient-rich waters of Casco Bay produced the most delectable mussels he’d ever tasted.

Knowing that he alone didn’t represent sufficient demand to get Bangs Island distributed to Colorado, Reilly jokes that he became the “Johnny Appleseed of mussels,” talking them up to fellow chefs (such as Matt Vawter, who recently left Denver’s Mercantile Dining & Provision to open Rootstalk in Breckenridge) and urging Denver-based Seattle Fish Co. to take Bangs Island on as a vendor.

“We know that we can’t make the change that we want by ourselves. It’s all about collaboration.”

Derel Figueroa, Seattle Fish Co.

The supplier agreed: After all, Seattle Fish Co. has prioritized sustainability since 2008, when it first started partnering with such organizations as the Marine Stewardship Council and Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch. These colleagues have helped Seattle Fish to understand the science of sustainability and evaluate its vendors through that lens. “We either find vendors that operate sustainably, or we work with our existing partners to help them improve,” explains Derek Figueroa, Seattle Fish Co.’s president and CEO.

Figueroa also founded Sea Pact, a nonprofit to fund conservation projects across the globe, with five (now nine) of the largest U.S. seafood distributors. Plus, he chairs the seafood industry’s trade group, the National Fisheries Institute. “That has given us a good vehicle to collaborate with the really big operators and effect the changes that yield the most impact,” says Figueroa. “We know that we can’t make the change that we want by ourselves,” he adds. “It’s all about collaboration.”

Yet Figueroa also values his relationships with small producers such as Bangs Island Mussels, because that company’s pioneering approach to sustainable aquaculture deserves to be scaled up. Seattle Fish Co. introduces Bangs Island to new sales outlets and tells its story to a broader audience. “Maine is small, so for us to succeed, we need to leave the state,” says Matt Moretti, the second-generation mussel farmer who runs Bangs Island (and now also sees his product in Chicago and Atlanta). Selling to Seattle Fish Co. has allowed Moretti to expand his business and invest in better methods; last year, he switched to 100 percent biodegradable and food-safe bags and tags, which are twice as expensive. “But with the advantage of scale, it works fine,” says Moretti, who believes increasing mussel production on his farm and others promises tremendous environmental benefit. “They’re one of those perfect foods that are incredibly nutritious, yet are inexpensive and have minimal environmental impact, so at maximum scale, this is an animal that can sustainably feed the masses.”

Moretti is seeking sustainability solutions underwater, but another collective of chefs and restaurateurs is working to restore the land. San Francisco-based chef Anthony Myint founded Zero Foodprint to fund soil regeneration projects via a one-percent surcharge paid by diners at participating restaurants. Last year, Zero Foodprint expanded to Colorado, where restaurants and caterers have been quick to sign on. DiFranco’s in Denver, GB Culinary and Whistling Boar in Longmont, Bin 707 Foodbar in Grand Junction, River and Woods in Boulder, and all of Boulder’s Subway locations are among the businesses that have so far committed to the Zero Foodprint program, which funnels donations to Colorado farms that combat climate change with regenerative practices that sequester carbon dioxide into the soil.

“These are such big issues, but like a lot of people, we didn’t know what to do to truly make a difference,” says Whistling Boar co-owner and private chef Debbie Seaford-Pitula. Zero Foodprint did that research, and established a pathway for improvement. “We just give one percent. And all we’ve heard from our customers is, ‘Yes! This is wonderful!’ Because I don’t think any of them knew what to do either,” says Seaford-Pitula.

Incredible though it may seem, Whistling Boar and other food businesses are successfully recruiting patrons to pay extra for something as abstract as soil health. This act of scaling up by staying small points to the exacting power of collaborative action. This is precisely where independent restaurants leverage their own power—by coming together, they truly can sustain the food industry as a whole. Because where restaurants lead, diners will follow.

Talk to us! Email your experiences (and thoughts, opinions, and questions—anything, really) to askus@diningout.com.

Comments are closed.