The Accidental Landlord

Like most restaurateurs, Chris Schmidt works long days. That’s to say nothing of the 30-minute drive from his home in Gypsum to his restaurant, Craftsman, in Edwards, and the hour and 10 minutes (assuming dry roads, no traffic or road closures) up and over Vail Pass to his second restaurant, Bird Craft, in Frisco. On a typical day, Schmidt gets up around 7 a.m., then spends an hour or so with his family while catching up on emails before he climbs into his gray Ford F-150 to drive to his restaurants, often returning home in the black of midnight.

Under normal circumstances, Schmidt would drive to Frisco only once a week for a quick meeting with his manager and kitchen staff, but this year is far from normal. For most of the summer, Bird Craft was without a chef or sous-chef, short on line cooks and dishwashers. Schmidt drove over the pass several times a week to fill in where necessary—on the line, scrubbing floors, washing dishes. In the last week of July, he worked more than 50 hours at Bird Craft alone so that his general manager there could take some time off. “Every hour I spend covering shifts or working the line, the further behind I fall as a business owner,” Schmidt says.

It’s no secret that restaurants across the nation are struggling to find staff. In July, the Colorado Restaurant Association reported that more than 90 percent of restaurants in the state were having difficulty hiring. Reasons for the workforce shortage (which has affected many U.S. businesses outside of the hospitality industry, as well) abound. Much blame was attributed to extended pandemic unemployment benefits that ended September 4. But the labor shortage extends beyond U.S. borders—reportedly as far as France and South Africa—indicating a widespread exodus from the hospitality industry since the beginning of the pandemic. Is it the result of burnout? Job insecurity? Inadequate wages? A search for a better work-life balance? The answer is all of the above and more.

There are also the parents—primarily mothers—who were forced to leave their jobs to care for their children when COVID mandates forced daycare centers and schools to close. According to a recent report by the National Women’s Law Center, 36.4 percent of the nearly 5.1 million net jobs women lost in the past year were in the leisure and hospitality industry. All combined, these factors have created the perfect storm.

“Every hour I spend covering shifts or working the line, the further behind I fall as a business owner.”

Chris Schmidt, Craftsman and Bird Craft

If that weren’t enough, operators in Colorado’s mountain resorts have yet another, potentially larger, hurdle as they frantically attempt to lure workers: housing. Access to affordable housing has been a problem in ski towns for decades, but, combined with post-COVID staffing issues, it has driven some restaurant owners to take on employee housing single-handedly.

The staffing shortage appears much worse in the state’s mountain towns than its metro areas. Resort towns are brimming to overcapacity with visitors. Even on traditionally slow days, like Mondays, towns are bustling. After mandated closures and capacity restrictions, restaurateurs in these small towns should feel relieved to see the crowds, but instead of ushering them into their restaurants, many of these establishments must turn customers away. “Every restaurateur I know, especially in the mountains, is just dying for staff,” Schmidt says. “People are closing one to two days a week, because they’ve got nobody to run the restaurant.”

“We’ve made the decision, like I know a lot of other restaurants have… to only operate five days a week,” says Jaimie Mackey, who, with her husband Caleb, opened the Assembly in Eagle in August 2020. Even at five days a week, they are short-staffed. Phil Armstrong, founder of the Destination Hospitality group, which owns four restaurants in Steamboat Springs and Breckenridge (with two more opening, one of which will be in Snowmass), remembers how grateful he felt in summer 2020 to be an operator in the mountains, where business was strong despite the pandemic. Meanwhile, metro businesses scrambled for customers. “Now, we’re in a way worse situation,” he says. Severely short-staffed, Armstrong is “choking revenue” and limiting nightly reservations to ensure he doesn’t burn out and lose any of the staff he does have because there’s no one to take their place. “I’m in preservation mode. It’s the single biggest thing that has threatened our industry that I’ve faced in the 30 years I’ve been doing this.”

Restaurateurs are using every incentive in the book to entice employees this year: pay raises, tip pools, service charges, signing bonuses, retention bonuses, referral bonuses, health benefits, parking benefits, cell phone benefits, ski passes—“the kitchen sink,” as Paul Landry, vice president of Revpar International, a hospitality advisory and asset management company with a branch in Golden, says. He’s only partly joking. “I’ve been doing restaurants for the better part of 30 years now and I’ve never quite seen it as bad as it is in terms of staffing and labor,” he says. “It’s a constant battle for us every day right now.”

In ski towns like Aspen, Breckenridge, and Steamboat Springs, some restaurateurs have added housing to their arsenal of employee benefits. In places like these, where the tourism-based economy is seasonal and the workforce is largely comprised of transient 20-somethings in search of the ski-bum lifestyle (who rarely intend to stay in town more than a season or two), finding dependable staff with a strong work ethic has long been difficult. Even if an employer could find a qualified, reliable candidate willing and able to work, formidable housing costs were often still a hurdle. It’s an age-old story, but COVID changed the story line—housing costs have become insurmountable.

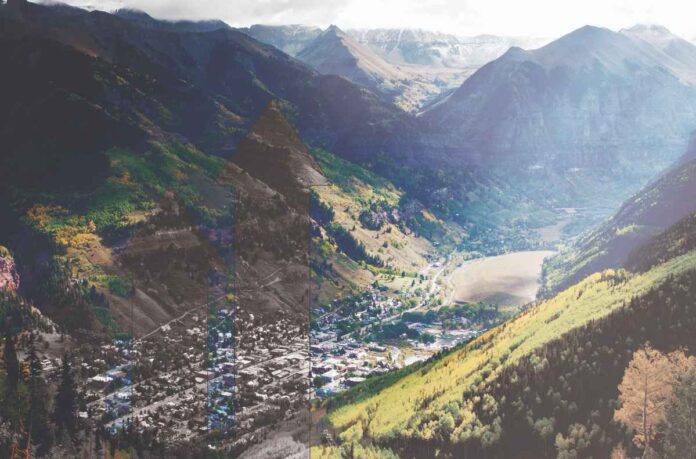

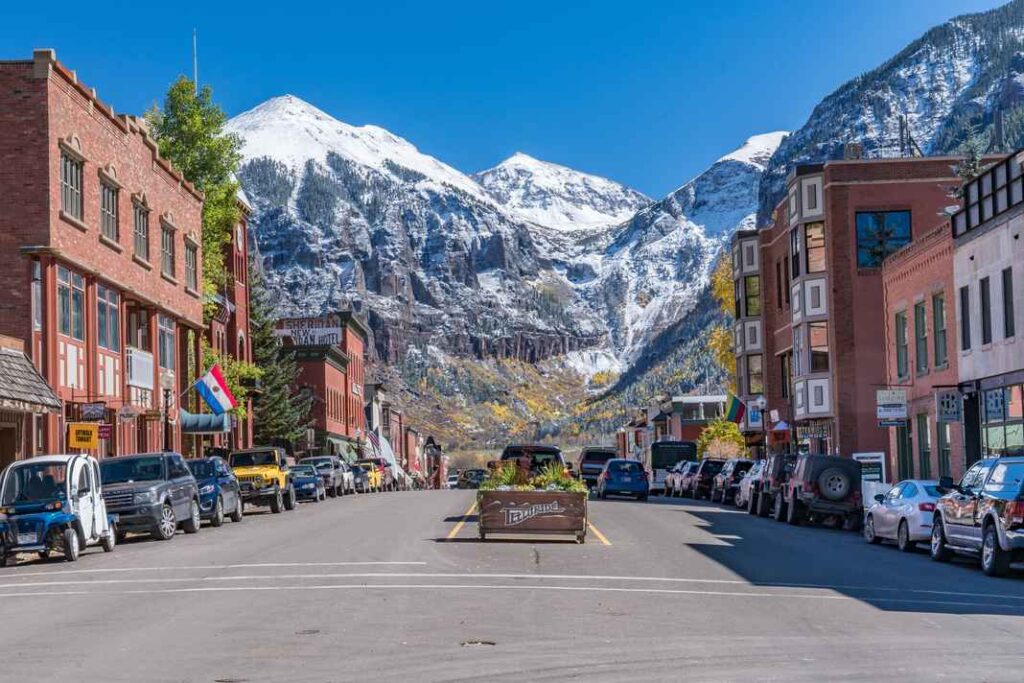

“Affordable housing has always been a challenge in a mountain destination like Telluride,” explains Annie Carlson, of the Telluride chapter of the Colorado Restaurant Association. “However, COVID took that challenge to an astronomically high new level.” COVID refugees, as they’ve been termed, flocked to mountain towns during the pandemic. Second homeowners who previously spent a few weeks per year at their mountain homes decided to ride out the storm there. And they still haven’t left. People from around the country, no longer leashed to their office desks, sold their urban homes and relocated to Colorado’s resort towns.

According to the Mountain Migration Report released in May by the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments and the Colorado Association of Ski Towns (CAST), this sudden influx of the wealthy and über-wealthy into mountain towns has created a real-estate frenzy. High demand and low inventory have led to cash offers and bidding wars, driving housing prices to record highs. Between 2019 and 2020 alone, the average price of homes in these areas increased by as much as 55 percent, and home prices continue to soar this year. Per the report, Grand County recorded the lowest average home price of $670,000 in 2020, but in Pitkin County, the average home price was closing in on $4.5 million. An increasing number of long-term residents are being displaced as the homes they’ve rented for years are purchased by wealthy newcomers. The rental supply is dwindling, and both purchase and rental prices are escalating beyond locals’ reach.

“As an employer and small busines owner like myself, to provide employee housing is a very difficult task to accomplish.“

Eliza Gavin, 221 South Oak

“I think we have one to two employees a week, or every couple weeks, come to us and say ‘I’m looking for a new place,’” says Breckenridge restaurateur Ken Nelson, who owns multiple restaurants including Sancho Tacos & Tequila and Briar Rose Chophouse & Saloon. By the middle of summer, Nelson was still short about 40 employees between his four restaurants. “It makes sense that as housing becomes more scarce, employees are more likely to become more scarce as well,” says CAST’s executive director, Margaret Bowes. “The housing issue is feeling like a crisis.”

Indeed, as hard as these communities have worked over the years to create affordable and accessible workforce housing, there have never been enough units to meet the need. And this year, the scarcity has skyrocketed. Earlier this summer, The Colorado Sun reported the Town of Frisco considered issuing an official emergency declaration due to the housing issue. And it’s not just Colorado mountain towns. Ketchum, Idaho, which sits five minutes from Sun Valley Resort, is also desperate. In July, The Wall Street Journal reported the mayor of Ketchum suggested the town allow a tent city in the municipal park so workers would have a place to live.

Situated in a box canyon in the San Juan Mountains in the remote southwest corner of the state, Telluride is among the Colorado resort towns hardest hit by the housing shortage. “In the past, you would hear of a few people here and there not being able to find a place to live,” Carlson says. “Now it’s imminent. It’s everywhere. It’s the only thing people are talking about.”

Chad Scothorn, owner of Cosmopolitan, has lived and worked in Telluride for 26 years. Even at its swollen post-pandemic population of about 2,500 residents, Telluride is still a tiny town. “In resort towns like Telluride, if you want really good employees like a manager, a sous-chef, or a pastry chef… you need to be able to recruit nationwide,” he says. “The problem with recruiting nationwide is you can fly them in and you can interview them and you can offer them a good salary, but once they get here and they see how bad the housing situation is, they never take the job.”

Housing has been a stumbling block to hiring and retaining good employees for so long in these towns that many operators have considered buying property for employee housing. But doing so isn’t easy and isn’t without risk. Even before COVID, the cost was prohibitive and the financial risk substantial. “It’s not for everybody and it’s hard to do,” Nelson says. “But everybody has a key employee—or three—that they need to find housing for. The ability to do that for a business makes a lot of sense.”

“If we do it, we’ll look at it as not only an investment for the business… but we’re also investing in the business by hopefully retaining employees and having an opportunity to get better employees,” says Schmidt. Of course, buying employee housing in the midst of the post-COVID real-estate landscape is far from ideal or, for many, remotely realistic. “As an employer and small business owner like myself, to provide employee housing is a very difficult task to accomplish,” says Eliza Gavin, owner and chef at 221 South Oak in Telluride.

And let’s not forget that becoming a landlord—especially a landlord of one’s own employees—has very real drawbacks. “My biggest concern… if you needed to terminate somebody for any sort of inappropriate behavior on the job… not only are you firing them and they don’t have a job, but you also are evicting them out of their home,” Mackey of the Assembly says. “What a horrible position to be in. I don’t want to have anything to do with controlling or policing my employees’ personal lives.” For now, the Mackeys are using a different tactic to help their employees find housing near their Eagle restaurant: “We’re going to guarantee a lease for them,” she explains. “If they don’t pay rent, we’re on the hook… but we’re prepared to put our faith into it to help our employees get housing, because we don’t want them to have to leave the county.”

In a similar move, Armstrong’s Destination Hospitality has begun to lease properties in order to sublease them to employees. “Our networking in these towns is pretty strong and we’re a reliable tenant,” he explains, while stressing it’s not a money-making endeavor. The housing isn’t cheap, nor is his approach without risk or headache; Armstrong had four employees/tenants come and go in just three months this summer. “I’m not super interested in being a landlord, it’s just become almost a necessity. The eight bedrooms I have against 150 employees… obviously, that math isn’t great, but at least it’s something.”

“Sometimes it really does feel like doing whatever you can—as ridiculous as it might sound in the moment—if that’s what it takes to keep the doors open.“

Jaimie Mackey, the Assembly

In Telluride, Cosmopolitan’s Scothorn has not only purchased property for employee housing, but he has done so aggressively. “I think if you want to be a successful business, you need that as a recruiting device,” he explains. “The only way I’m going to be able to work less is to hire better people, and I believe the only way I can hire better people is to offer them a better package that includes… good housing, because it’s hard to find here. It’s really hard to find.” Scothorn had already purchased two properties, with a total of four bedrooms, before COVID. With a staff of 45, that’s not much, he admits, but he is in the process of building homes on land he’s purchased in Norwood, a small town of about 500, roughly 45 minutes away from Telluride. Scothorn is hopeful some longtime second homeowners he knows will invest in his employee-housing project. He’s gone as far as to offer to be their property manager—without the traditional 30 to 40 percent management fee. “I’ll simply make sure it’s rented to my employees, and if I can’t rent it to my employees, I’ll have no problem finding [others.]”

Scothorn’s Norwood housing project isn’t without its drawbacks, however. Though San Miguel Authority for Regional Transportation (SMART) offers free public transportation between Telluride and Norwood, it doesn’t operate during the late-night hours that restaurant workers would need, so Scothorn is also tackling transportation between the two towns for his employees. He hopes to convince SMART to offer van service for late-night staff or he will pay his employees with cars to drive those without.

Of course, that would expand Scothorn’s resume to restaurateur, employee-housing developer, landlord, property manager, and transportation manager. So be it, he says. Scothorn has taken on each and every one of these jobs with one sole purpose: to find and retain the employees he needs for his Telluride restaurant to thrive. “Desperate times call for desperate measures,” Mackey confirms. “Sometimes it really does feel like doing whatever you can—as ridiculous as it might sound in the moment—if that’s what it takes to keep the doors open.”

Talk to us! Email your experiences (and thoughts, opinions, and questions—anything, really) to askus@diningout.com.