Why do we keep doing this? Why get up each day to face the crush of shit we know awaits us? Why get on the treadmill to run the marathon when we’re just standing still? Exhaustion without progress; survival without a clear future.

Why, why, why?

It’s our moment of existential crisis, right? Our old pro formas and strategic plans may as well line birdcages, along with the rest of yesterday’s news. You can’t do what we do without having asked yourself the question: What, in the name of Julia Child, is the bloody point of it all?

In so many ways we’re sharing the raw ingredients of this experience: fear and insecurity and frustration and fatigue and inspiration and drive and creative energy and, and, and…and yet, we’re each experiencing it in our way, those ingredients stirred in various measurements and heated to different temps and served on everything from paper plates to fine china. We find it within ourselves to forge forward, intermittently fighting the urge to curl up in the walk-in, precisely because of our version of “why.” But without the answer, we all know this work would be straight-up undoable.

So we asked for some familiar folks to share their answers in their own words. Their responses were as diverse as their menus—equal parts heartbreak and inspired vision. They draw on the responsibilities and burdens of leadership and stewardship and passion and community, and on opportunities camouflaged in the rubble.

We had more responses than pages, so we’ve excerpted many of them, but the full essays (along with words from Joe Ouellette and Fetien Gebre-Michael) will appear online, and we hope you’ll add your voice to the collection because, as Mr. Rogers once said, “Anything that’s mentionable is manageable.” And if we do it together, we can manage the living shit out of this thing.

We begin with Juan Padro, group partner at Culinary Creative and owner of several award-winning restaurants, whose voice has become an integral measure of what it means to lead in an ever-changing environment.

Juan Padro: Make Space at the Table for More Ideas

My father was a fun-loving, jovial character from Puerto Rico with a big accent and a bigger heart. Everyone who came within five feet of him was sure to be engulfed in one of his famous bear hugs, whether he knew you or not. He loved first and asked questions later. Above all, my father taught me to have a passion for people. That passion is what ignites my sense of purpose, and it’s what led me to the restaurant industry. When I was asked to write this piece, I thought to myself, “This will be easy; it’ll just roll off my tongue and onto the keyboard.” But I was wrong. What gets me up in the morning? While the answer to that question will always be people, the context today is very different from 2010 when I opened my first store. The stakes are higher now that we own nine restaurants in two cities. And there are a lot more people.

It’s been over a decade since I left corporate America and moved across the country to open Highland Tap & Burger with my former wife (and current business partner and confidant) Katie O’Shea. We built everything we have from the ground up with hard work, lots of love, and a set of values that remain unchanged. When you walked into Highland Tap 10 years ago, you were greeted with a big hug and a smile. The business mirrored the Puerto Rican culture embodied by my father: lots of people, all of them welcomed and encouraged to be themselves.

“It turns out your “why”—like any living thing—has to evolve or it becomes irrelevant. “

I thought I had it answered because I’d long ago defined my “why.” Anyone who’s seen Simon Sinek’s famous—and excellent—TEDx Talk about the “why” in business understands. But it’s not that easy. It turns out your “why”—like any living thing—has to evolve or it becomes irrelevant.

This spring, the world ground to a halt. A crippling pandemic followed by a modern-day civil rights movement, and all of it has challenged us as business owners—and as humans—to lead, to be inclusive and accountable, to create opportunity for people of color and our brothers and sisters in the LGTBQ community, and to put humanity in front of profit. It’s forced me to reflect on the world around me, and dig deep to answer the not-so-simple question, “How do we move forward?”

One of my mentors, the world-renowned humanitarian Dr. Alison Thompson (who I worked with to bring aid to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria), once said, “It’s leadership to be at the wrong place at the right time.” For all of us in the restaurant industry, 2020 has to be the wrong place. But it is without question the right time to move forward, to leverage this opportunity to lead our businesses and our industry into the future.

Leadership means going beyond traditional roles. We must get involved with our communities in a way that alters the decades to come. We cannot prosper until those who we serve prosper. We cannot measure our success solely by profitability. We must measure it by what we’ve helped create. And we must protect those who are most vulnerable, at all costs.

From my vantage point, it begins by putting more seats around the table. Inclusivity changes the conversation and the solutions. I saw this as the protests overwhelmed our city. I formed a leadership group within my organization, challenging this group to come up with ways to make us better, so that our words of support were reflected in our actions. This council isn’t made up of managers, but is focused on developing a diverse group of young leaders who represent different races, ethnicities, genders, and sexual orientations.

And you know what? It’s been one of the best business decisions I’ve made. We’ve already partnered with a teen-run nonprofit, engaged Khesed Wellness to provide mental health services to the underinsured within our organization, and added an inclusivity statement to our mission. In just six weeks, we’ve begun to outline a future as a company that encourages diverse ideas and listens to the needs of our people.

“What gets me up in the morning is the idea that we might seize this moment to celebrate a new way forward.“

People. As always, they are our company’s—and our community’s—greatest asset. I think of my father often. He made it his life’s work to create opportunities for the disadvantaged. One of his weaknesses—and consequently one of mine—is that we’ve had our ideas about how that should look. Leaders tend to be authoritarian by nature. Their ideas may be born of good intentions, but they’re uncollaborated, and thus unleveraged. Leaders’ ideas suffer when there aren’t enough people at the table. Once we pulled up the chairs, the conversation is what brought those ideas to life.

So, what gets me up in the morning? The answer is still people, but it’s more conscious now, more inclusive, more open. We are better together—better leaders and better citizens. What gets me up in the morning is the idea that we might seize this moment to celebrate a new way forward: one that honors all people in the interest of a more sustainable, more inclusive future [that’s] full of opportunity for everyone. I’m inspired by the idea that leaders of all colors, backgrounds, and sexual orientations will emerge from our ranks, if we let them, to impact Denver and move us forward as a shining example for America and for the world.

Click here to read Padro’s complete op-ed.

Like Juan Padro, Jensen Cummings (chef and founder of the popular Best Served podcast) also finds his motivation in lifting people up. Cummings’ show is dedicated to meeting the unsung heroes of the industry, “sharing their needs, struggles, aspirations, and talents.” He came up in kitchens, a descendent of five consecutive generations of restaurant families. At 18, he began washing dishes at his uncle’s restaurant. It was there, he says, “I found my tribe…my island of misfit toys….I caught the hospitality fever, and there was no turning back….”

Jensen Cummings: The Why and Who Before What and How

It was thrilling to be immersed in the heat of the kitchen and I craved the feelings of elation and exhaustion after a kick-ass (and ass-kicking) service, that moment when we knock out the last ticket and lock eyes—from exec chef to dish. It’s hard to explain this bond to anyone who has never worked in a restaurant. As a result, I seldom try. After finally burning out and leaving the kitchen, I spent the last six years struggling to find a purpose. If I am neither a chef nor a restaurant owner, who am I? My own shortcomings have manifested a single word that drives me and my show: Acknowledgement.

The industry gets so caught up in the minutiae of what we do and how we do it that we forget why we get out of bed to do what we do, and who it is that we serve. Staying tethered to those ideals is what actually gets us through the hard times, which, in the restaurant industry, are inevitable. We spend all of our time focusing on what is on the plate, rather than who gets it to the plate. Because of this, we often miss out on what truly matters—who truly matters. I am damn lucky that I now spend my days speaking with such inspired and inspiring people at every level and every facet of our food and beverage ecosystem. These people are why I get out of bed in the morning. They are who I serve.

Click here to read Cummings’ entire op-ed.

“We do this because we love people,” agrees Caroline Glover, chef and co-owner of the nationally esteemed Annette in Aurora. And while she attests that she and her husband and business partner Nelson Harvey have changed their definition of hospitality, shifting from, “The guest is always right” to, “We’re all in this together,” that basic mission of “people first” remains at the core of her motivation. No more suffering intolerant guests or worrying over inane reviews; now, more than ever, she is tireless in her commitment to connection. “People need a place to gather, to find solace from the difficulties of daily life, and to celebrate its milestones,” she says. “We are such a place.”

Caroline Glover & Nelson Harvey: At the Heart of Hospitality

This pandemic has made plain a fact that has been easy to forget: There are no guarantees. How long will our current business model work? How long can we stay open? Somehow, before the pandemic, we thought we knew the answers to these questions. We never did.

Over the course of three and a half years, we have built a community that gathers each week around food. We are open for them: For the single guy with the mysterious government job who once joked that he would call in a bomb threat if we ever took the egg salad off the menu. For the salty-tongued neighborhood woman who showers us with baked goods at every opportunity. For the retired couple who appears each Wednesday for rosé and popcorn, often bearing thoughtful gifts for our staff. For the elderly woman who calls each week to report her harvest of some obscure garden herb, wondering if we can put it on the menu. For the young couple with four kids who escapes to Annette late at night. For the local acupuncturist with myriad food allergies who is still somehow obsessed with our butter- and sugar–filled biscuits. Our food gives these people pleasure. They give it back to us by showing up each week.

Click here to read Glover and Harvey’s full op-ed.

And then, there are those who have simply determined that their “why” is rooted in their being, attached to them like a shadow, shortening and elongating with the angle of the sun, but always a part of who they are. Carmela Sanna, owner of La Piazza, La Pizzeria, and Rustico Ristorante in Telluride says, “Eating together unites us. Our customers’ friendship and gratitude gives us the encouragement to keep serving. We are reminded every day how lucky we are to be in this majestic little town in this incredible state. Restaurants, to us, are endless love.” (Click here to read Sanna’s full statement.) Just down the road, in the same magnificent San Juan box canyon, Ross B. Martin, owner of the National, agrees, “Memories around a table, with all the smells, taste, conversation, laughter, and sometimes tears, are some of the most ingrained memories we have…”

Ross B. Martin: We Do What We Love Because We Must

Gathering around for a meal is one of the oldest traditions of mankind; it will never die, never disappear, never cease to exist. We will wake up every day and do what we love to make sure it never does. We make memories and experiences—food, drink, and service are our tools.

Click here for Martin’s full musings.

“It feels like a much easier decision to simply close and start finalizing payments for outstanding invoices,” admits Brother Luck, chef-owner of Four by Brother Luck and Lucky Dumpling in Colorado Springs. “If there were an ideal time to get out of the hospitality business, this would be it.” Instead, Luck keeps his head up and soldiers on.

Brother Luck: The Herd Marches Together

I remind myself that I’m only composing a chapter and not the finale. I go to bed each evening thinking about solutions to the challenges I’ve encountered throughout my day and how I can solve them for my family at large.

Yesterday I heard a story about Colorado buffalo that resonated. These massive animals walk headfirst into storms on the horizon because they understand they can get through them faster by embracing the uncomfortable. Cattle, on the other hand, walk away from the storm, thus prolonging the inevitable and enhancing their fear of the discomfort. I refuse to run from the storm of 2020 because I know that once it passes, there’s a picturesque rainbow waiting.

Click here for all of Luck’s words.

Perhaps nobody wields these tools with more finesse than Dana Rodriguez, executive chef and proprietor of Denver’s Work & Class and Super Mega Bien. Anyone who’s encountered her incomparable spirit knows that it is simply a part of her essence to embrace and celebrate humanity through the medium of food.

Dana “Loca” Rodriguez: Por Que es lo Que Amamos y Lo Que Sabemos Hacer (Because it is What We Love, and What We Know How to Do)

Seguimos aquí por que debemos respeto a las familias que an sido porte de nuestro crecimiento, por que somos parte de la economía de nuestro país. Y también por que es nuestra manera de dar un poco de lo que tenemos. Seguimos aquí por que tenemos pasión y respeto por la comida, nuestra cultura y nuestra ética profesional. Aunque por dentro estemos debatidos, afligidos, deprimidos y hasta enfermos, siempre saldremos adelante con una sonrisa en nuestro rostro para compartir lo que producimos y para dar un poco de esperanza al mundo con una sonrisa que significa que todo estará bien.

We keep going because we owe respect to the families that have been part of our growth, because we are part of our country’s economy. It is also because it’s our way to give a little of what we have. We keep going because we have passion and respect for food, our culture, and our professional ethic. Even though on the inside we may be distraught, beaten, depressed, or even sick, we will always move forward with a smile on our face—to share what we produce, to give a little hope to the world, with a smile that means everything will be all right.

Click here to read all of Rodriguez’s thoughts (in both Spanish and English).

A little hope. A smile that means everything will be all right. Hosea Rosenberg, chef-owner of Blackbelly and Santo in Boulder, is a model of strength and perseverance, finding deep perspective in a storm that, for him and his wife Lauren, rages on multiple fronts…

Hosea Rosenberg: The Answer Hasn’t Really Changed Since Forever Ago

When I was younger, I would often have to talk myself back into the grind with, “Well, at least people will always need to eat.” I needed to reassure myself when I was hitting the fifteenth hour without a proper meal or a break, and knowing I was not making enough money to afford anything fun, that I was doing something worthwhile. It wasn’t about money. It was about fulfilment. Fulfillment was the idea that my work made others feel good. People need to eat.

Am I happy right now? Not really. My daughter was diagnosed with a terrible disorder the same week we were told to shut down our dining rooms. She is the most important thing in my life, and her disease will get worse over time; it has no cure and no treatment. I should be working on that all the time—and on nothing else. At the restaurants, the staff is constantly scared they’re going to get sick, no matter the safety precautions or added protections. The financials suck. Sales are way down. We are just trying to get through this without going out of business. Some of the guests are rude and not very understanding. The pressure and the fear is always looming.

But would I rather be doing something else? Absolutely not. Despite all of it, this is still my happy place, even if I’m not happy at this very moment. There is something uniquely rewarding about restaurant life.

We thrive off of the challenge. We love pushing through the tough stuff. We are a community, a family. We are stronger together. We need each other. We support each other. Why? The answer has always been the same: Why not? The people need to eat. And we need to feed them.

Click here for Rosenberg’s complete op-ed.

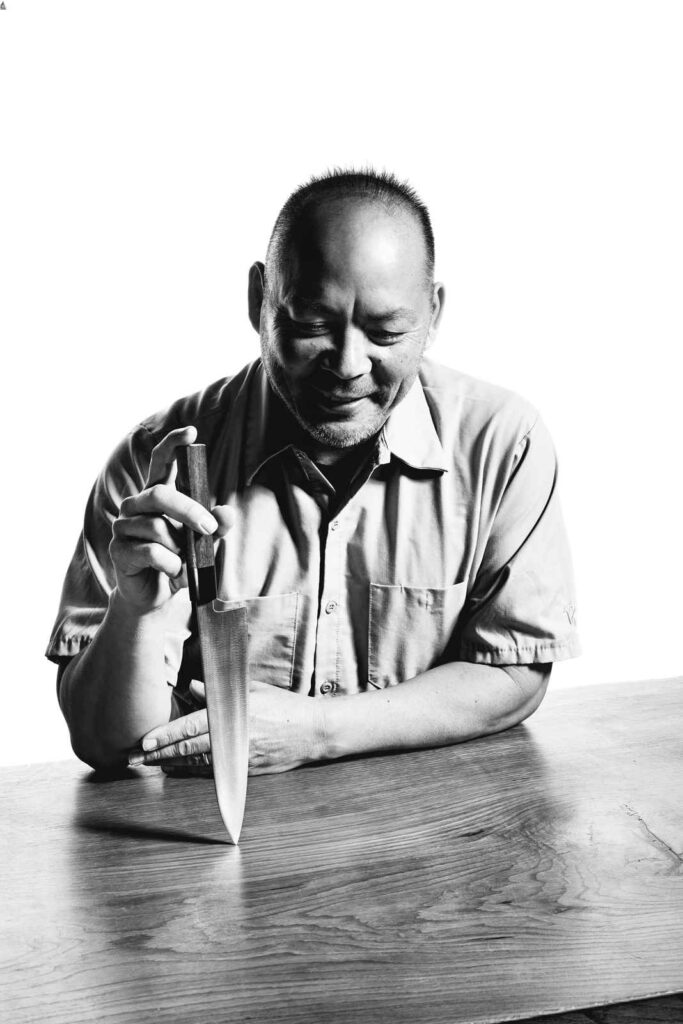

Chef Jeff Osaka, like so many of us, knows well the highs and lows of restaurant ownership, the always tenuous grip on survival of even the most wildly popular and critically adored kitchens. Like so many others, he bears the weight of his responsibility, and understands that the imminent danger in coming to love a thing is the very real risk of losing it.

Jeff Osaka: And, Still, Life Goes On

Things die. In the past six months, I was forced to close a restaurant permanently, a chef friend of mine died unexpectedly in front of his young daughter, and three people in my organization have taken their own lives.

How do I continue to live a life of my own, yet be a cheerleader to others? How do I continue to champion an industry where I’ve given my heart and soul, when the odds are against me the moment I wake each day? I’m exhausted before I start my day and I can’t sleep at night. I’m tired of being tired. I beat myself up with the heaviest of guilt knowing I might have been able to prevent someone’s death: “If only I said this…or did that.” What is this all for if you can’t help those around you?

I’ve worked hard to hone my craft in the kitchen, but as it turns out, cooking is the easy part. People depend on me; our guests come to our restaurants to put life on pause for a few precious moments. I survive on the people who exist around me, and the memories of those who have left us. I strive to be a better employer, father, husband, and my reward at the end of the day is when I can tell myself, “Today was a great day!”

Click here for an unedited version of Osaka’s words.

At his restaurants Bin 707 Foodbar, Tacoparty, and Bin Burger in Grand Junction, chef-owner Josh Niernberg laments the chronic struggle. He has fought to keep the vast majority of his staff employed from the beginning and has continued to purchase from all of his independent suppliers, despite 30 percent less revenue in over 25 percent more shifts. “That alone was our mission when we started 10-plus years ago,” he says, “and…in this respect, we are doing OK, but we won’t make it past January with this model. Something has to change…again.”

Josh Niernberg: I Rise Each Day and Do the Work

The main issue we all face isn’t the restrictions, the reduced business, the risk of getting sick, the threat of going out of business, or even the treatment we are all subjected to by following and enforcing guidelines. No, it’s the effort required to adapt and change for the next set of challenges. That is crippling. I’m dizzy from pivoting. No other industry or group could even begin to understand what we have all been subjected to and are navigating daily.

The set of challenges I face are unique to me. Every single operator has an impossible list just like mine. The constant that remains is that this is our industry. We understand it. We speak its language. We love it even when we hate it. And this grueling chapter brings us to how we can be better.

Click here for Niernberg’s full op-ed.

Indeed, Andrea Frizzi, chef-owner of Il Posto and Vero in Denver, is motivated most by the symbiotic relationship between guest and restaurant, and inspired by the soul that a thoughtful kitchen can imbue into an otherwise soulless landscape.

Andrea Frizzi: We Are Here Because

We are here because we are part of the heart and creativity of the community. A restaurant creates a little village with patrons, waitstaff, managers, cooks, and dishwashers. We see you and you see us. We remember your birthday, you celebrate your anniversary with us. We ask you about your vacation to the Grand Canyon, you think of us on vacation when you order that bottle of wine we suggested. We’re forced to close and pivot, you order takeout and try our to-go cocktails. We are here because we are living organisms, and any city without a vibrant restaurant community would just be an assembly of buildings and concrete.

Click here for Frizzi’s full op-ed.

As restaurateurs, we surround ourselves with people, both those on our staff and those at our tables. A focus on people is innate to success in the industry. But like so many things we do as humans, our focus (often out of necessity) can be so trained on the here and now that we lose sight of our larger impact. Daniel Asher, esteemed chef-partner at Boulder’s River and Woods, Denver’s Ash’Kara, Barrio75 in Ketchum, Idaho, and several forthcoming projects, cares for the people around him at his own expense, and spends most working evenings putting out fires, both actual and figurative. Asher has also spent his adult life advocating for the health of the planet, and so, even in the grip of the current crisis, he works to remember the purpose he’s defined for himself: utilizing the canvas of his restaurants to help paint a world that’s worth passing forward.

In meeting San Francisco-based chef Anthony Myint, he was introduced to Zero Foodprint, a program that harnesses the power of restaurants to repair the very earth from which we source our ingredients and build our menus. The program is immediately impactful, addressing, quite literally, the root of the problem.

Daniel Asher: “Why” Only Matters If There’s A “What” to Put It On

My mind goes to that scene in The Breakfast Club when Anthony Michael Hall’s character is pressed to define, “Who am I?” The definitions hover—chef, restaurateur, employer, father—everything attached to a role, an expectation. But strip those away, and what’s left is simply this: human. We’re all just humans, zipping around the planet, trying to find shelter, food, love, and a sense of purpose.

Last summer during the Slow Food Nations conference (remember those?), my path intersected with Anthony Myint, an award-winning chef-restaurateur turned carbon farming advocate. The effects of carbon are no longer a revelation: In the atmosphere, it’s a major contributor to climate destruction; in the soil, it increases fertility and water retention and limits the need for chemical fertilizers. In the simplest terms, carbon farming utilizes a diverse methodology of growing and ranching practices to sequester CO2 in the earth (where it’s healthy) rather than it escaping to the atmosphere (where it’s not).

“Sustainability. We’ve buzzworded it into meaninglessness. But it’s not meaningless.“

Sustainability. We’ve buzzworded it into meaninglessness. But it’s not meaningless. It’s not just a satire of woke culture on Portlandia. It is quite literally the difference between life and death. At a time when we’re all fearing the loss of the very things that define us—when we’re confronted daily to reassert our “why”—I am reminded that our calling is to feed people. In so doing, our responsibility is to help ensure that’s possible now, tomorrow, and into the next generations.

For myself, beyond the basic restaurant model, there exists a desire to accomplish more: to inspire curiosity and create change within those 90 minutes I have with a stranger at my table. Over the years, my advocacy has been focused on plant-based cuisine, sustainable local food systems, promoting organic agriculture, combating food waste, and debating why there is such an imbalance of food equity causing millions of people daily to live with food insecurity. This is all good work, and it is deeply meaningful to me. Yet, after more than two decades of advocacy, less than two percent of the land in America is organically farmed, heirloom vegetables and pasture-raised proteins are too expensive for 90 percent of our own communities to afford to eat, and the actual business model of running restaurants is in itself an exercise in madness. We haven’t moved the needle.

A few minutes into our very first conversation, Anthony mused, “Delaying the inevitable isn’t exactly the best marketing slogan, so let’s dive into the power we have to promote good farming. Saving the entire planet can come down to restoring the soil a few acres at a time.” He had an intense expression and carried a copy of the book Drawdown, and I quickly realized that this conversation was going to shift my perception of how to use restaurants as a medium for change. Anthony introduced me to Zero Foodprint (ZFP), a nonprofit effort to have restaurants crowdfund grants (via a one percent surcharge on checks) to help farmers switch to renewable practices. Healthy soil, he said, could sequester all the carbon humans emit every year. And it’s doable.

“…Our calling is to feed people….Our responsibility is to help ensure that’s possible now, tomorrow, and into the next generations.“

In the year that followed that first meeting, a lot of things happened in the world. You know, global chaos and such. But meanwhile, Anthony received the Basque Culinary World Prize for utilizing gastronomy as a transformational motor of change—and the James Beard Foundation named the ZFP program Humanitarian of the Year. He launched a collaboration with the State of California to scale regenerative agriculture. More than 100 restaurants participated in San Francisco Restaurant Week, with one percent of revenues going to fully vetted carbon farming initiatives.

And using that momentum, Anthony has navigated into a partnership with Mad Ag, a Boulder-based nonprofit that aims to “reimagine and restore our relationship with the earth through agriculture.” ZFP has aligned with the cities of Denver and Boulder and multiple regional agencies, and the organization is poised to “go all-in, and create a focused, systematic change mechanism instead of just advocating for different choices in the broken food system.” Anthony is turning that approach on its head. “Historically,” he says, “the good food movement has been about getting people to eat the $20 burger instead of the $1 value menu burger. Instead, we need to get an extra few cents per burger to enable farmers to scale to regenerative agriculture.”

These changes can be massively impactful. A recent study on a section of livestock ranch in Marin County showed that carbon ranching on 600 acres, a single mid-sized ranch, could sequester enough carbon to recover the CO2 emissions from more than 258,000 gallons of gasoline. There are more than 770 million acres of range- and grassland in the U.S. alone.

“We all know that everything about our food system—all the way from the farm to the table—is broken.“

I love Anthony’s brand of functional rebellion, and it inspires me to demand more answers. We all know that everything about our food system—all the way from the farm to the table—is broken, and it sure feels like now is the time to address some fixes. We’re not likely to change a profit-driven model to one of social justice on any kind of scale, but while the system is gutted, we may as well do some renovation. Maybe we can’t change the feedlot model by wagging a finger at it, but we can add compost to the land the cattle are raised on before they enter the feedlot. Solutions are the easy part; scientists and agroecologists have them at the ready. The hard part is getting buy-in from large corporations that basically need someone to prove to their board of directors that doing these things can be publicly beneficial and profitable.

As I talk to Anthony about including the ZFP surcharge and messaging at my restaurants, I try to push for some vulnerabilities in his theories—something, anything, that has not been clearly contemplated. “Anthony, where did this materialize? How did cooking become so complicated and why, in the midst of the current hospitality implosion, should we worry about something else that’s going horribly wrong?” He parleys effortlessly, saying, “Project Drawdown demonstrated that we can reverse climate change at a cost of only one percent of our gross domestic product, with the positive impact to our healthcare system and overall planetary wellness in the trillions of dollars. Why wouldn’t we use our restaurants as an immediate lifeline for those projects?”

I want to be a part of that. Don’t you want to be a part of that?

I believe in my soul that we are all inextricably connected. By doing everything we can to ensure that our planet is covered in fertile, vital, biodiverse soil, we are helping to create a living web of nourishment that literally sustains everything. I can’t really think of anything more inspiring, or a better way to frame the importance of the work we do in our kitchens. I, at once, feel overwhelmed, anxious, and eager to get busy. Thanks, Anthony, for redefining why the hospitality industry is where I have immersed myself for 28 years.

He leaves me with this: “If legitimately being part of the solution is this easy, then why not? We’re assuming our guests, like us, want to be part of the solution. It’s on us to take care of them, and to make it easy for them to support local climate solutions. It’s $1 on a $100 check. Guests can always opt out. But the system is too broken to perpetuate business as usual. We need a new normal. One percent seems like a small price to un-fuck the planet.”

Click here to read Asher’s stand-alone statement.

Zero Foodprint launches in Denver and Boulder with its first round of member restaurants this fall. Bin 707 Foodbar in Grand Junction is already actively contributing to the program. It costs nothing to be a part of Zero Foodprint, and the potential returns are profound. While we’re fighting for our own sustainability, we may as well fight for the earth’s. To learn more, visit zerofoodprint.org.

What is your “why”? Email your experiences (and thoughts, opinions, and questions—anything, really) to askus@diningout.com.